In vitro compatibility between Rhizobium sp. (CIAT 899) and strains of Trichoderma asperellum Samuels, Lieckfeldt & Nirenberg and Pochonia chlamydosporia (Kamyschko ex Barron and Onions) Zare Gams

Main Article Content

Abstract

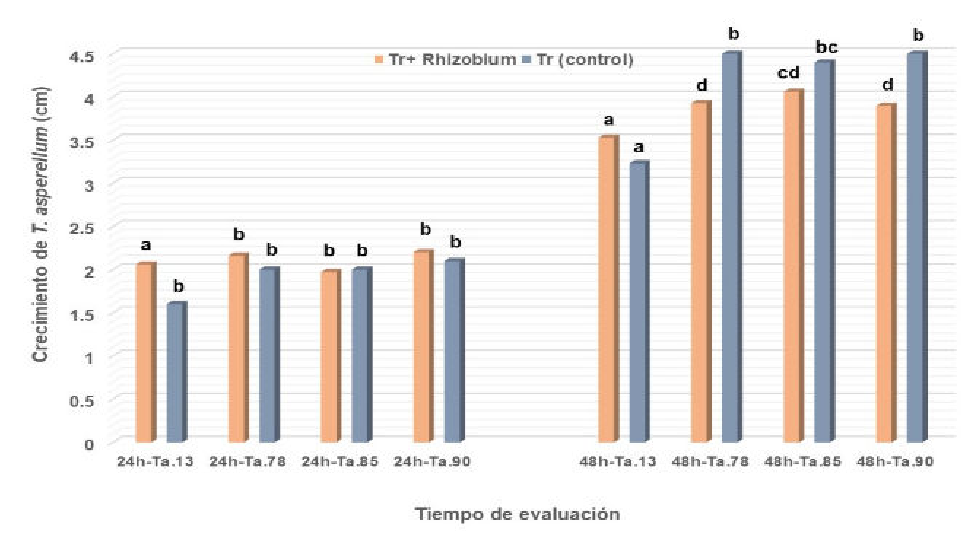

The present work was developed with the objective of evaluating the in vitro compatibility of Trichoderma asperellum Samuels, Lieckfeldt & Nirenberg, and Pochonia chlamydosporia (Kamyschko ex Barron and Onions) Zare and Gams with Rhizobium biofertilizer (CIAT 899). The dual culture technique was used to determine compatibility by evaluating antibiosis (prior to their contact with the Rhizobium colony; at 48 hours and ten days) and competition for space (according to the grade scale referred to by Bell and the calculation of the percentage of the radial growth inhibition). Prior to the contact, the colonies of T. asperellum and P. chlamydosporia showed an inhibitory effect with respect to the control; with no significant differences in the case of P. chlamydosporia. At 96 hours, the Trichoderma strains were in grade 1 on the scale referred to by Bell, while Pochonia was in grade 2 at 18 days. Compared with the control, the evaluated strains of Trichoderma did not show inhibition to Rhizobium at 96 hours; Pochonia showed a decreasing effect with 2.5 % inhibition at 18 days.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Aquellos autores/as que tengan publicaciones con esta revista, aceptan los términos siguientes:

- Los autores/as conservarán sus derechos de autor y garantizarán a la revista el derecho de primera publicación de su obra, el cual estará simultáneamente sujeto a la Licencia Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) que permite a terceros compartir la obra, siempre que se indique su autor y la primera publicación en esta revista. Bajo esta licencia el autor será libre de:

- Compartir — copiar y redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato

- Adaptar — remezclar, transformar y crear a partir del material

- El licenciador no puede revocar estas libertades mientras cumpla con los términos de la licencia

Bajo las siguientes condiciones:

- Reconocimiento — Debe reconocer adecuadamente la autoría, proporcionar un enlace a la licencia e indicar si se han realizado cambios. Puede hacerlo de cualquier manera razonable, pero no de una manera que sugiera que tiene el apoyo del licenciador o lo recibe por el uso que hace.

- NoComercial — No puede utilizar el material para una finalidad comercial.

- No hay restricciones adicionales — No puede aplicar términos legales o medidas tecnológicas que legalmente restrinjan realizar aquello que la licencia permite.

- Los autores/as podrán adoptar otros acuerdos de licencia no exclusiva de distribución de la versión de la obra publicada (p. ej.: depositarla en un archivo telemático institucional o publicarla en un volumen monográfico) siempre que se indique la publicación inicial en esta revista.

- Se permite y recomienda a los autores/as difundir su obra a través de Internet (p. ej.: en archivos telemáticos institucionales o en su página web) antes y durante el proceso de envío, lo cual puede producir intercambios interesantes y aumentar las citas de la obra publicada. (Véase El efecto del acceso abierto).

References

Fijación Biológica de Nitrógeno Atmosférico. El nitrógeno y su importancia. INTAGRI. 2018. Disponible en: https://www.intagri.com/articulos/nutricion-vegetal/fijacion-biologica-de-nitrogeno-atmosferico. (Consulta: 2 agosto 2022)

Fijación Biológica de Nitrógeno: Plantas y Bacterias. 2022. Disponible en: https://eos.com/es/blog/fijacion-biologica-de-nitrogeno/(Consulta: 2 agosto 2022)

Cuadrado B, Rubio G, Santos W. Caracterización de cepas de Rhizobium y Bradyrhizobium (con habilidad de nodulación) seleccionados de los cultivos de fríjol caupi (Vigna unguiculata) como potenciales bioinóculos. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Quím. Farm. 2009; 38 (1): 78-104.

Mikhailova N. El uso equilibrado de fertilizante gracias a las técnicas nucleares contribuye a aumentar la productividad y a proteger el medio ambiente. Boletín del OIEA. 2020. Disponible en: https://www.iaea.org/es/newscenter/news/el-uso-equilibrado-de-fertilizante-gracias-a-las-tecnicas-nucleares-contribuye-a-aumentar-la-productividad-y-a-proteger-el-medio-ambiente. (Consulta: 8 agosto 2022)

Nagananda GS, Das A, Bhattacharya S, Kalpana T. In vitro studies on the effects of biofertilizers (Azotobacter and Rhizobium) on seed germination and development of Trigonellafoenum-graecum L. using a novel glass marble containing liquid medium. Int J Botany. 2010; 6 (4): 394-403.

Boraste A, Vamsi K, Jhadav A, Khairnar Y, Gupta N, Trivedi S, et al. Biofertilizers: a novel tool for Agriculture. Int J Microbiol. 2009; 1 (2): 23-31.

Sadowsky MJ. Competition for nodulation in the soybean / Bradyrhizobium symbiosis. En: Triplett EW. (Ed.). Prokaryotic nitrogen fixation. Horizon Scientific Press. Wymondham, UK. 2000; 279 pp.

Samuels GJ. Trichoderma: a review of biology and systematic of the genus. Mycol Res. 1996; 100 (8): 923-935.

Bader AN, Salerno GL, Covacevich F, Consolo VF. Bioformulation of Trichoderma harzianum in solid substrate and effects of its application on pepper plants. Rev. Fac. Agron. 2020; 119 (1): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.24215/16699513e037.

Arévalo J, Hidalgo-Díaz L, Martins I, Souza JF, Castro JMC, Carneiro RMDG, et al. Cultural and morphological characterization of Pochonia chlamydosporia and Lecanicillium psalliotae isolated from Meloidogyne mayaguensis eggs in Brazil. Tropical Plant Pathology. 2009; 34 (3):158-163.

Ceiro-Catasú WG, Hidalgo-Viltres M, Hidalgo-Díaz L, Arévalo-Ortega J, García-Bernal M, Mazón-Suástegui JM. Establecimiento in vitro del hongo nematófago Pochonia chlamydosporia var. catenulata en diferentes suelos. Terra Latinoamericana. 2021; 39: 1-7. e792. https://doi.org/10.28940/terra.v39i0.792.

Larriba E, Jaime MDLA, Nislow C, Martín NJ, López LLV. Endophytic colonization of barley (Hordeum vulgare) roots by the nematophagous fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia reveals plant growth promotion and a general defense and stress transcriptomic response. Jour. of Plant Research. 2015; 128 (4): 665-678.

Camargo-Cepeda D, Ávila E. Efectos del Trichoderma sp. sobre el crecimiento y desarrollo de la arveja (Pisum sativum L.). Ciencia y Agricultura. 2014; 11 (1): 91-100.

Zhao L, Zhang Ya-qing. Effects of phosphate solubilization and phytohormone stress. Jour. of Integrative Agriculture. 2015; 14 (8): 1588-1597.

Hoyos-Carvajal L, Duque G, Orduz S. Antagonismo in vitro de Trichoderma spp. sobre aislamientos de Sclerotinia spp. y Rhizoctonia spp. Rev. Colombiana de Ciencias Horticolas. 2011; 2 (1): 76-86.

Lopez-Llorca LV, Gómez-Vidal S, Monfort E, Larriba E, Casado-Vela J, Elortza F, et al. Expression of serine proteases in egg-parasitic nematophagous fungi during barley root colonization. Fungal Genetics and Biology. 2010; 47: 342-351.

Kerry BR, Hirsch PR. Ecology of Pochonia chlamydosporia in the rhizosphere at the population, whole organism and molecular scales. En: Daviers K, Spiedel Y (Eds). Biological Control of Plant-Parasitic Nematodes. Springer Netherlands. 2011; 171-182.

González-Marquetti I, Infante-Martínez D, Arias-Vargas Y, Gorrita-Ramírez S, Hernández-García T, de la Noval-Pons BM, et al. Efecto de Trichoderma asperellum Samuels, Lieckfeldt & Nirenberg sobre indicadores de crecimiento y desarrollo de Phaseolus vulgaris L. cultivar BAT-304. Rev. de Protección Veg. 2019; 34 (2): 1-10.

Salina Ventura R, Boriano Bonilla B. Efecto de Trichoderma viride y Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense en el crecimiento de Capsicum annuum en condiciones de laboratorio. REBIOLEST. 2014; 2 (2): e32.

Bécquer CJ, Ramos Y, Nápoles JA, Dolores AM. Efecto de la interacción Trichoderma-rizobio en Vigna luteola SC-123. Pastos y Forrajes. 2004; 27 (2): 139-145.

Martínez B, Solano T. Antagonismo de Trichoderma spp. frente a Alternaria solani (Ellis & Martin) Jones y Grout. Rev. Protección Veg. 1995; 10 (3): 221-225.

Bell K, Wells D, Markham R. In vitro antagonismo of Trichoderma species against six fungal plant pathogers. Phytopathol. 1982; 72: 379-382.

Samaniego G, Ulloa S, Herrera S. Hongos del suelo antagonistas de Phymatotrichum omnivorum. Rev. Mex. Fitopatología.1989; 8: 86-95.

Di Rienzo JA, Casanoves F, Balzarini MG, González L, Tablada M, Robledo CW. InfoStat [programa de cómputo]. Córdoba, Argentina: Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. 2017. Disponible en: http://www.infostat.com.ar/.

Woo L, Lorito M. Exploiting the interactions between fungal antagonists, pathogens and the plant for control. En: Vurro M, Gressel J (Eds). Novel Biotechnologies for Control Agent Enhancement and Management. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: IOS, Springer Press. 2007; 107-130.

Talibi I, Boubaker H, Boudyach EH, Ait Ben, Aoumar A. Alternative methods for the control of postharvest citrus diseases. Jour. Applied Microbiol. 2014; 117 (1): 1-17.

Twelker S, Oresnik LJ, Hynes MF. Bacteriocins of Rhizobium leguminosarum. A molecular analysis. Highlights of nitrogen fixation research. En: Martínez E. &, Hernández G (Eds). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York. 1999;20: 105

Bécquer CJ, Lazarovits G, Lalin I. Interacción in vitro entre Trichoderma harzianum y bacterias rizosféricas estimuladoras del crecimiento vegetal. Revista Cubana de Ciencia Agrícola. 2013; 47 (1): 97-102.

Castro-Toro M, Rivillas-Osorio A. Trichoderma spp. modos de acción, eficacia y usos en el cultivo de café. Boletín Ténico Cenicafé. 2012; 38: 31 pp.

Lorito M, Woo SL, Harman GE, Monte E. Translational research on Trichoderma: from "omics" to the field. Annu Rev. Phytopathol. 2010; 48: 395-417.

De la Cruz-Quiroz R, Roussos S, Rodríguez-Herrera R, Hernández-Castillo D, Aguilar CN. Growth inhibition of Colletotrichum gloesporioides and Phytophthora capsici by native Mexican Trichoderma strains. Karbala Int. J. of Modern Science. 2018; 4: 237-243.

Hoyos-Carvajal L, Duque G, Orduz S. Antagonismo in vitro de Trichoderma spp. sobre aislamientos de Sclerotinia spp. y Rhizoctonia spp. Rev. Colombiana de Ciencias Horticolas. 2011; 2 (1): 76-86.

Freitas-Chagas Junior A, Gonçalves de Oliveira A, Rodrigues dos Santos G, Barbosa- Reis H, França-Borges Chagas L, Oliveira-Miller L. Combined inoculation of rhizobia and Trichoderma spp. on cowpea in the savanna, Gurupi-TO, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Agrárias. 2015; 10 (1):27-33.

Hoyos-Carvajal L, Orduz S, Bissett J. Growth stimulation in bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) by Trichoderma. Biological Control. 2009; 51 (3): 409-416.

Mweetwa AM, Chilombo G, Gondwe BM. Nodulation, nutrient uptake and yield of common bean inoculated with Rhizobia and Trichoderma in an acid soil. J. Agric. Sci. 2016; 8 (12):61-71.

Tanusree Das, Sunita Mahapatra, Srikanta Das. In vitro Compatibility Study between the Rhizobium and Native Trichoderma Isolates from Lentil Rhizospheric Soil. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2017; 6 (8): 1757-1769.

González-Marquetti I, Ynfante-Martínez D, Gorrita S, Morales-Mena B, Nápoles MC, Peteira Delgado-Oramas B, et al. Efectos de Trichoderma asperellum Samuels, Lieckfeldt & Nirenberg y Azofert ® sobre el crecimiento y desarrollo de Phaseolus vulgaris L. Rev. de Protección Veg. 2021; 36 (3):1-9.

Zaki MJ, Ghaffar A. Combined effects of microbial antagonists and nursery fertilizers on infection of mung bean by Macrophomina phaseolina (Tassi) Gord. Pakistan Phytopatology. 1995; 1: 17.

Tsimilli-Michael M, Eggenberg P, Biro B, Köves- Pechy K, Vörös I, Strasser RJ. Synergistic and antagonistic effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Azospirillum and Rhizobium nitrogen-fixers on the photosynthetic activity of alfalfa, probed by the polyphasic chlorophyll a fluorescence transient O- J-I-P. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2000; 15 (2):169-182. ISSN 0929-1393, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1393(00)00093-730

Moreira H, Pereira SIA, Vega A, Castro PML, Marques APGC. Synergistic effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-promoting bacteria benefit maize growth under increasing soil salinity. J. Environ Manage. 2020; DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109982.

Kavadia A, Omirou M, Fasoula DA, Louka F, Ehaliotis C, Ioannides IM. Co-inoculations with rhizobia and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi alters mycorrhizal composition and lead to synergistic growth effects in cowpea that are fungal combination-dependent. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021; 167: 104013.

Zare R, Gams W, Evans HC. A revision of Verticillium section Prostrata. V. The genus Pochonia, with notes on Rotiferophthora. Nova Hedwigia. 2001; 73: 51-86.

Puertas A, de la Noval BM, Martínez B, Miranda I, Fernández F, Hidalgo-Díaz L. Interacción Pochonia chlamydosporia var. catenulata con Rhizobium sp., Trichoderma harzianum y Glomus clarum en el control de Meloidogyne incognita. Rev. Protección Veg. 2006; 21 (2): 80-89.

Siddiqui IA, Shaukat SS. Combination of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pochonia chlamydosporia for Control of Root-Infecting Fungi in Tomato. J. Phytopathology. 2003; 151: 215-222.

Monteiro Avelar TS. Ação combinada de Pochonia chlamydosporia e outros microrganismos no controle do nematoide de galhas e no desenvolvimento vegetal. [Tese doctor scientiae]. Universidadde Federal de Viçosa, Brasil. 2017. 100 pp.